Interlocking Action

How Cooperation Within Organizations is Key to Combating Transnational Crime

📅 February 27, 2025

📅 February 27, 2025

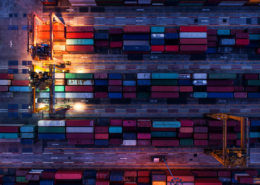

Transnational crimes – such as trafficking, smuggling, and cybercrime – are valued at more than $2 trillion annually, and more than 80% of the world’s population lives in countries with high levels of exposure to criminality. To counter the destructive effects on economies and individuals, coordinated action is required.

For the public sector, the powers of law enforcement are constrained by national boundaries, and international cooperation is required to extend action beyond them. For the private sector, regulatory requirements are established and enforced by each country. For example, privacy requirements—justifiably put in place to protect citizens’ information—often constrain movement of data across borders. While the need for international cooperation by law enforcement and other government agencies is well-established and there have been successes—as described below—there is scope for further action within private sector organizations.

Some types of criminality are by their nature transnational. For example, for narcotics trafficking or the illegal wildlife trade, the sources of trafficked products are often different from their key markets. To provide another example, countries and entities subject to sanctions and export controls—such as Russia and Iran—seek components from western countries because items cannot be produced domestically, or are of lower quality than components sourced internationally. In both examples, the illicit procurement networks sourcing these items must, by definition, move them internationally from their origin to their intended use or final market.

Criminal networks may also deliberately use international activities in an attempt to obscure the financial trail and make it more difficult to follow. For example, they may use shell or front companies registered in different jurisdictions from the buyer or seller, cross-border payments routed through third countries, or transshipment points. Physical items may be moved along different travel routes than the corresponding financial flows. These all aim to increase the difficulty of public and private sector organizations to “follow the money.” However, international cooperation can still achieve success.

Successful Action Against a Transnational Criminal Network: Operation Destabilise

A real-life example of how coordinated joint action can be effective against transnational criminal networks is Operation Destabilise. This Operation, led by the United Kingdom National Crime Agency (NCA), achieved success in 2024 against an organized criminal network spanning multiple countries. The origin of the funds laundered by the network included the proceeds of several types of criminal activity, including the proceeds of ransomware.

In the United Kingdom, the organized crime group used a network of operatives to receive handovers of cash. For these handovers, there was a corresponding movement of crypto of the same value paid to the criminal network. The funds were used by the criminal network to purchase weapons and drugs.

The global network involved more than 30 countries, including the UK, Middle East, South America and Russia. The network was also linked with a company registered in Thailand which facilitated export of electronic components to Russia.

In addition to the NCA, the success of the Operation Destabilise was the result of cooperation with the United States (OFAC, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the Drug Enforcement Agency), France (Direction Centrale de la Police Judiciaire), Ireland (An Garda Síochána), and authorities in the UAE.

The outcomes so far include sanctions imposed by OFAC, 84 arrests, and seizure of more than £20m ($25m) in cash and crypto.

In the private sector, many organizations are also multinational, including financial institutions. This provides both strengths and weaknesses when detecting, disrupting, and preventing transnational crime.

As a foundation, all financial institutions must ensure their staff have sufficient training and experience on typologies and “red flags” associated with international criminal activity. Banks that operate only in limited geographical markets may still be a target for criminal networks, as was evident in the recent TD Bank enforcement action. Although TD Bank operated primarily in specific regions of the United States and Canada, its AML program failures resulted in it being targeted by illicit actors laundering proceeds of criminal activity from multiple high risk countries. Therefore, it is not only international or global financial institutions that are vulnerable.

In contrast, a multinational or global financial institution may have some advantages in countering illicit finance networks. These institutions may hold transaction and customer data on cross-border financial flows between their branches or subsidiaries in multiple countries. This provides the potential to enable internal investigative teams to “follow the money” beyond national borders and to map out more of the criminal network.

The limitation is that a multi-national financial institution will need to comply with regulations in multiple jurisdictions, such as those where there are restrictions on cross-border movement of data. To remain compliant with requirements such as data privacy—while also taking effective action against illicit activity—a bank will need to unify action internally between different stakeholders, including those beyond the financial crime compliance team.

We have seen the significant adverse consequences where an organization does not find the right solution.

Inadequate Internal Coordination: Enforcement Actions

Nordea (2024): Nordea’s International Branch served customers including those located in or beneficially owned by persons in Russia and Eastern Europe (referred to in Nordea as “East” customers). Some of these customers exposed Nordea to money laundering risks including the “Russian Laundromat” and “Azerbaijani Laundromat”. After Nordea made the decision to close its International Branch, the East customers sought to open accounts in Nordea’s Baltic branches and Luxembourg. Nordea was unable to monitor whether these exited customers were onboarded at other branches due to bank secrecy restrictions limiting sharing of customer information across branches.

Swedbank (2023): Swedbank engaged in transactions with a customer in a sanctioned region. Although the bank collected IP address data which indicated the customer’s location, it had not integrated this data into its screening processes.

HSBC (2012): HSBC Group did not inform its U.S. business, HSBC Bank USA, of significant AML deficiencies at HSBC Mexico, despite knowing that these problems existed. The result was the potential flow of hundreds of millions of dollars in narcotics trafficking proceeds from HSBC Mexico through HSBC Bank USA.

To fulfil their responsibilities to take action against transnational crime while also fulfilling national jurisdictional requirements, Chief Compliance Officers should:

By undertaking these actions, an organization will be able to provide the most effective response to transnational criminal networks while also fulfilling its regulatory obligations.

The Institute for Financial Integrity Wednesday hosted a webinar on the convergence of sanctions and financial crimes compliance featuring a panel of experts.

Key topics to be addressed include:

Russia: Slew of Sanctions

Russia: Slew of SanctionsThis site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site, you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

Accept settingsHide notification onlySettingsWe may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

These cookies collect information that is used either in aggregate form to help us understand how our website is being used or how effective our marketing campaigns are, or to help us customize our website and application for you in order to enhance your experience.

If you do not want that we track your visit to our site you can disable tracking in your browser here:

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

You can read about our cookies and privacy settings in detail on our Privacy Policy Page.

Privacy Policy